FOR SURE YOU DON’T KNOW THE MOST IMPORTANT PYTHAGORA’S THEOREM / TU NEJDŮLEŽITĚJŠÍ PYTHAGOROVU VĚTU URČITĚ NEZNÁTE

česká verze níže ↓

Everyone knows the name Pythagoras and most of us even remember from the school his famous theorem, which everyone used to know by heart. Only few, however, know that this well-known theorem wasn’t the only one which was worth the highlight and, above all, its integration into everyday life. The much more important Pythagorean message has remained hidden to this day.

Pythagoras of Samos, born around 570 BC, influenced a lot of famous thinkers like Plato, Aristotle or Isaac Newton. He regarded himself as an observer of nature and heaven. In his day, he was known as a founder of a new life. He was interested not only in mathematics, but also in music that he believed was purifying the soul. Pythagoras emphasized physical exercise, athletics, therapeutic dance, routine morning walks and morning and evening contemplation.

He also influenced and inspired many people with his ethical-vegetarian attitude. The very concept of vegetarianism originated in the 1840s. Previously, people who did not eat meat were referred to as „Pythagoreans.“ Pythagoras‘ most important thought, which is about the very essence of human life, expressed in three sentences is as follows:

“As long as Man continues to be the ruthless destroyer of lower living beings, he will never know health or peace. For as long as men massacre animals, they will kill each other. Indeed, he who sows the seed of murder and pain cannot reap joy and love.”

The question is whether it would be wiser to memorize these phrases, in which everything is contained, rather than a theorem about triangle and its legs. Why have these sentences been forgotten? Why didn’t they become famous? What would today’s heartless world look like if we would have followed this theorem?

The best-known preserved writings in which Pythagoras talks about vegetarianism are Ovid‘s Metamorphoses. In his speech, he calls on his followers to adhere to a strictly vegetarian diet that has a major impact on human life. Here’s a snippet:

“O you mortal beings, stop corrupting your own bodies with such defiling food. You have grain, apples weighing branches down, along with grapes which ripen on the vine. You can use fire to cook sweet-tasting plants and make them tender. There is no lack of milk or honey smelling of the fragrant thyme. Munificent Earth offers you her wealth, producing feasts of harmless things to eat, without the need for blood and slaughter.

Some beasts feed on meat, but many do not, for horses, sheep, and cattle live on grass. Those whose temperament is wild and savage – Armenian tigers, raging lions, bears, as well as wolves – delight in blood-soaked meat. How wrong it is to feed our flesh with flesh, to fatten up our gluttonous bodies by eating bodies, to let one creature live by bringing death to other living things!

Is it really true that, with all this wealth the Earth, the best of mothers, offers us, nothing pleases you unless your savage teeth bring back the eating habits of the cyclops and gnaw on pitiful wounds? Can you men not satisfy the ravenour hunger pangs inside your greedy and intemperate gut unless you butcher other living things?

That earlier time, which we call Golden, was happy with its harvests plucked from trees and crops the earth produced. Men did not stain their mouths with blood. Birds winged their way in safety through the air, hares roamed unafraid in open fields, and fish were not hauled up on hooks because there were so credulous. There was not treachery in anyone, no fear or fraud. All things were filled with peace.

Then someone, whoever he was, acting against the common good, was envious of what the lions ate, and stuffed raw meat into his greedy stomach, thus opening the road to crime. It may well be the case that at the start men’s gory swords grew hot from slaying animals, but that’s all right, for I concede that men may kil those beasts intent on killing them. That is no sin. But while such creatured may be put to death, it is not right for men to eat them, too. From that time on the wickedness spread further.“ You can find the extended wordings here: http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/ovid/ovid15html.html.

But Pythagoras was not the only thinker who was interested in animals and their close links with our lives. Famous people who avoided meat consumption included Albert Einstein, Arthur Schopenhauer, Mahatma Gandhi, Friedrich Nietzsche, Isaac Newton, Nikola Tesla, Spinoza, Seneca, Thomas Edison, Plato, Socrates and many others.

These thinkers and explorers had in common that they thought about things that were fundamentally important and that affected their lives and the world to a great extent. Is today’s excessive and adored meat consumption associated with the fact that people have stopped thinking?

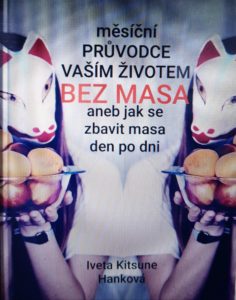

Perhaps now is the right time for us to think about this Pythagorean idea and start to follow it. This important message had to wait several centuries when it is discovered. Now it is up to each of us to integrate it into our daily lives. It is never too late for a reassessment and a fundamental change from which everything else will gradually unfold. Admitting that we have been doing something wrong the whole time is not easy. But it is much worse to never find out.

Každý zná jméno Pythagoras a většina z nás si i pamatuje ze školních lavic jeho slavnou větu, kterou všichni museli znát nazpaměť. Už jen málokdo však ví, že tato věta, kterou se proslavil, nebyla jediná, která stála za vyzdvižení a především její začlenění do každodenního života. Mnohem důležitější Pythagorovo poselství nám tak až dodnes zůstalo skryto.

Pythagoras ze Samu, který se narodil kolem roku 570 př. n. l., ovlivnil svou filosofií spoustu známých myslitelů jako byl Platon, Aristoteles nebo Isaac Newton. On sám se pokládal za pozorovatele přírody a nebes. Ve své době byl označen za zakladatele nového způsobu života. Zabýval se nejen matematikou, ale i hudbou, o které byl přesvědčen, že čistí duši. Důraz kladl i na fyzický pohyb, atletiku, terapeutický tanec, každodenní ranní procházky a ranní a večerní rozjímání.

Spoustu lidí také ovlivnil a inspiroval svým eticko-vegetariánským postojem. Samotný pojem vegetariánství vznikl až ve čtyřicátých letech 19. století. Předtím byli lidé, kteří nekonzumovali maso, označováni za “Pythagorejce“. Pythagorova nejdůležitější myšlenka, týkající se samotné podstaty lidského života, vyjádřena ve třech větách zní takto:

„Tak dlouho, jak bude člověk necitelným vrahem ostatních živých stvoření, nepozná zdraví a klidu. Tak dlouho, jak budou lidé zabíjet ubohá zvířata, budou se zabíjet navzájem. Ten, kdo zasévá sémě vražd a bolesti, nemůže sklidit radost a lásku.“

Otázka je, zda by nebylo moudřejší učit žáky nazpaměť spíše tyto věty, ve kterých je obsaženo naprosto vše, než větu o trojúhelníku a jeho odvěsnách. Proč se na tyto věty zapomnělo? Proč se neproslavily právě ony? Jak by vypadal dnešní bezcitný svět, kdybychom se řídili právě těmito větami?

Nejznámějším dochovaným spisem, ve kterém má Pythagoras proslov o vegetariánství, jsou Metamorfózy od Ovidia. Ve svém proslovu vyzývá své následovníky, aby dodržovali striktně vegetariánskou dietu, která má zásadní vliv na život člověka. Zde je z něj úryvek:

„Lidé, hříšným jídlem se varujte poskvrňovati těla! Obilí máte a ovoce, které svou tíhou sklání haluze k zemi, a na révě nalité hrozny; máte i rostliny sladké a takové, které se mohou zjemnit a změkčit v ohni; a nikdo vám mléčného moku nebere, nebere med, jenž voní mateřídouškou. Hýřivě dává země jak bohatství, tak také pokrm lahodný, dává co jísti, a bez vraždy, prolití krve.

Masem ukájí hlad jen zvěř, a ještě ne všechna! Například kůň a brav i skot, ti travou se živí; ti však, jejichžto duch jest surový, divý a krutý, tygřice z arménských hor a lvové vznětliví, vzteklí, medvědi, jakož i vlci – ti z krvavých těší se hodů. Běda, ach, jaký to zločin, když maso se do masa noří, dravé a lačné tělo když tuční polknutým tělem, když jest živočich živ zas jiného živoka smrtí!

Při tomto bohatství všeho, jež země, ta nejlepší matka, rodí, tebe snad těší jen žvýkati zuřivým chrupem žalostné kusy masa a řídit se Kyklópů mravem? Cožpak bude ti možno jen záhubou jiného tvora ukojit žaludku hlad, té neslušné, hltavé šelmy?

Ale ten dávný věk, jejž sami jsme nazvali zlatým, toliko stromů plody a rostlinstvem ze země vzešlým docela šťastným se cítil a ústa si neztřísnil krví. Pernatci za oněch dob si létali bezpečně vzduchem, zajíc, prost vší bázně, se proháněl uprostřed polí, v liché důvěřivosti se nechytla na háček ryba. Bez nástrah bývalo všechno a nebylo třeba se báti podvodu, všude byl mír.

Když jakýsi škodlivý rádce, nechať to kdokoli byl, se lvům jal závidět jídlo, a když masitou stravu si v hltavý žaludek spustil, zločinu otevřel cestu. Snad hubením divokých šelem zahřál se nejprve kov, když teplou krví se ztřísnil (na tom pak mohlo se zůstat!), a připouštím, nebylo hříchem, byla-li zabita zvěř, jež život náš ohrožovala; avšak zabíjet měla se jen, ne předkládat k snědku! Bezpráví zašlo pak dále.“ Rozšířené znění můžete najít zde: https://sites.google.com/site/novamisantropovacitarna/ovidius-promeny.

Pythagoras však nebyl jediným myslitelem, který se zamýšlel nad zvířaty a na jejich úzkém propojení s našimi životy. Mezi známé osobnosti, které se vyhýbaly konzumace masa, patřil například i Albert Einstein, Arthur Schopenhauer, Mahatma Gandhi, Friedrich Nietzsche, Isaac Newton, Nikola Tesla, Spinoza, Seneca, Thomas Edison, Platon, Sokrates a mnoho dalších.

Tito myslitelé a objevitelé měli společné to, že uvažovali nad věcmi zcela zásadními a ovlivňujícími ve velké míře jejich životy a celý svět. Je snad dnešní nadměrná a všemi zbožňovaná konzumace masa spojena s tím, že člověk přestal myslet?

Možná právě nyní nastal ten správný čas, abychom se všichni nad touto Pythagorovou myšlenkou zamysleli a začali se jí řídit. Toto důležité sdělení si muselo počkat několik století, až bude objeveno. Teď záleží už jen na každém z nás, jak ho začleníme do svého každodenního života. Nikdy není pozdě na přehodnocení a zásadní změnu, od které se pak postupně bude odvíjet naprosto všechno. Přiznat si, že jsme něco celou dobu dělali špatně, není lehké. Mnohem horší je to však nikdy nezjistit.